Source: CDC, Drew Harris

Credit: Connie Hanzhang Jin/NPR

As the coronavirus continues to spread in the U.S., more and more businesses are sending employees off to work from home. Public schools are closing, universities are holding classes online, major events are getting canceled, and cultural institutions are shutting their doors. Even Disney World and Disneyland are set to close. The disruption of daily life for many Americans is real and significant — but so are the potential life-saving benefits.

It's all part of an effort to do what epidemiologists call flattening the curve of the pandemic. The idea is to increase social distancing in order to slow the spread of the virus, so that you don't get a huge spike in the number of people getting sick all at once. If that were to happen, there wouldn't be enough hospital beds or mechanical ventilators for everyone who needs them, and the U.S. hospital system would be overwhelmed. That's already happening in Italy.

"If you think of our health care system as a subway car and it's rush hour and everybody wants to get on the car once, they start piling up at the door," says Drew Harris, a population health researcher at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. "They pile up on the platform. There's just not enough room in the car to take care of everybody, to accommodate everybody. That's the system that is overwhelmed. It just can't handle it, and people wind up not getting services that they need."

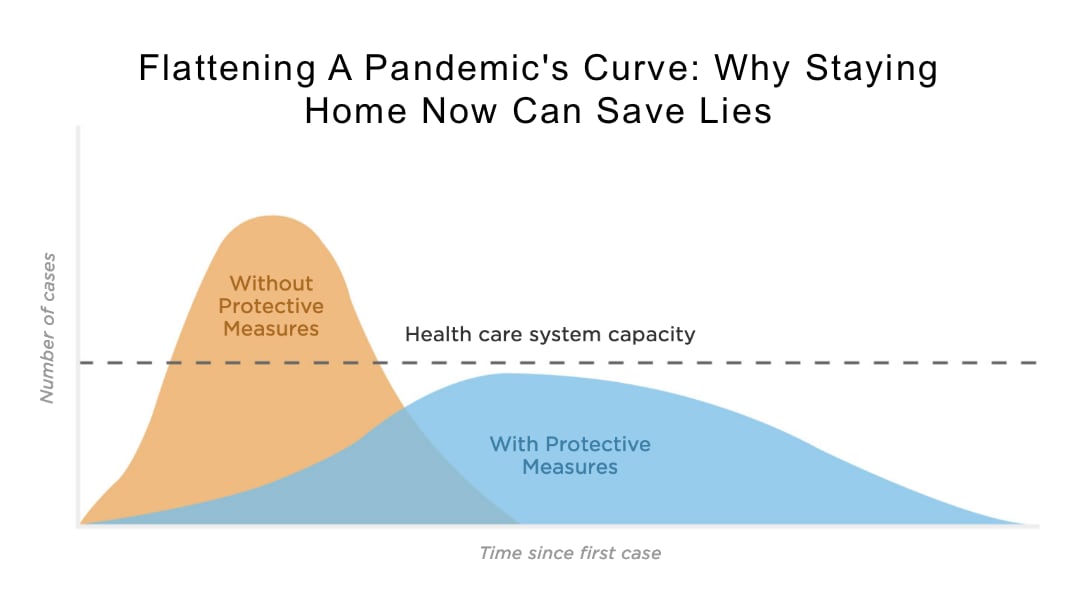

Harris is the creator of a widely shared graphic visualizing just why it is so important to flatten the curve of a pandemic, including the current one — we've reproduced his graphic at the top of this page. The tan curve represents a scenario in which the U.S. hospital system becomes inundated with coronavirus patients.

However, Harris says, if we can delay the spread of the virus so that new cases aren't popping up all at once, but rather over the course of weeks or months, "then the system can adjust and accommodate all the people who are possibly going to get sick and possibly need hospital care." People would still get infected, he notes, but at a rate that the health care system could actually keep up with — a scenario represented by the more gently sloped blue curve on the graph.